The Daze Of The

Knights

Donald stopped for a few

moments in the Upper Barrakka Garden and looked

outwards through one of the tall, modern,

limestone arches. Before him lay Malta’s

Grand Harbour, its turquoise-blue water whisked

into numerous white-topped peaks by the brisk

March wind.

Across the harbour stood

the ancient cities of Senglea and Vittoriose.

Donald gazed at the fortifications at the tip of

the peninsula on which Vittoriose stood - the 16th

Century walls of Fort St. Angelo. He reflected

that he must have studied the holiday brochure

with a greater intensity than he had recalled

because the view of those defences carried with

it a sense of deep familiarity - almost as if he

had been looking at a local landmark at home in

England.

Donald zipped-up his jacket.

The breeze was not cold by English standards -

Maltese people who had never visited the United

Kingdom had no concept of “cold by English

standards” - it was, however, not quite

comfortable, and so he turned around and made his

way from the Garden and towards the centre of

Valletta.

He had no

particular plan for the day so simply enjoyed

walking through the streets, taking-in the

atmosphere and looking at the orange-yellow

limestone buildings. Some had been constructed or

reconstructed after the Second World War. Others

had miraculously escaped the German and Italian

bombs but nevertheless displayed the scars of

battle in their stonework. At least some of these

buildings would have dated from the days of the

Knights. He had no

particular plan for the day so simply enjoyed

walking through the streets, taking-in the

atmosphere and looking at the orange-yellow

limestone buildings. Some had been constructed or

reconstructed after the Second World War. Others

had miraculously escaped the German and Italian

bombs but nevertheless displayed the scars of

battle in their stonework. At least some of these

buildings would have dated from the days of the

Knights.

Donald looked upwards.

Wooden balconies were perched on corbels

projecting from upper stories of the houses. Some

of the balconies were brightly painted in reds or

greens or blues. Others showed signs of neglect,

having long since lost any paint that had once

been applied to them. Washed clothes, in the

process of drying, fluttered frantically from

some, as if desperate to be carried away by the

blustering wind.

Donald stopped to take his

bearings and realised that he had reached the

dead centre of the city. He was standing outside

St. John’s Co-Cathedral. This was his first

visit to Malta, his first time in Valletta and

the first time he had seen the grand Cathedral of

the Knights of St. John. This sight, however,

once again engendered within him a strange sense

of familiarity. Without thinking, he ascended the

steps to the entrance of the Cathedral as if he

had habitually done so on numerous occasions.

It seemed to Donald that to

describe the interior of the Cathedral as

spectacular would have been an understatement.

Everywhere were intricate, elaborate carvings and

magnificent works of art. The nave and the side

chapels seemed to glow with a golden light,

reflected by the ornate Baroque decoration.

Donald paused at a side

chapel dedicated to one of the eight Langues -

the languages or nations into which the Knights

had been divided. ‘Don Miguel de Cordoba,’

he said, and stopped to wonder from where in his

memory that name had been awakened.

‘You are a scholar of

the Knights of St. John,’ said a voice from

behind him.

Donald turned to see an old

man in a black, flowing robe and the collar of a

priest. ‘I know virtually nothing about the

Knights,’ Donald replied to him.

‘How did you know

about Don Miguel de Cordoba?’ the man

enquired. ‘There are nearly four hundred

knights buried here, and Don Miguel was by no

means the most famous.’

‘I don’t know why

I said that name,’ said Donald, feeling

unsettled and perplexed. ‘...May I ask who

you are?’ he continued when he had recovered

his thoughts.

‘I’m Father

Augustus Acosta,’ said the man.

‘I’m the Cathedral historian.’

‘I’m Donald

Corren,’ said Donald. ‘I’m pleased

to meet you. Who was Don Miguel de

Cordoba?’

‘He was a Knight of St.

John,’ Father Acosta replied. ‘He came

to Malta in 1570 and lived here until he died in

1655. That period was part of a golden age for

the Knights. The Great Siege of 1565 was over and

had enhanced the reputation of the Knights,

leading to increased support from Europe. The

Knights were able to concentrate on developing

the island and enjoying their lifestyle.’

‘So, what did Don

Miguel do?’ asked Donald.

‘He was an

administrator,’ Father Acosta replied.

‘I’ve recently been looking into how

the Order managed the practicalities of everyday

life, so I’ve been studying those like Don

Miguel who oversaw the detail of routine affairs.’

‘I thought that

Knights travelled around, bravely righting wrongs

and undertaking chivalrous deeds,’ said

Donald.

‘There are a lot of

things that need to be done to maintain an Order

such as that of the Knights, not to speak of

running Malta,’ Father Acosta explained.

‘The Knights came from aristocratic families

across Europe. They were educated and so they

could write, discuss matters, plan and undertake

book-keeping.’

‘So, what was his life

like?’ asked Donald.

‘He would have

attended his office from nine in the morning

until five in the evening, with an hour for

luncheon. He would have had weekends off. That

was typical for "Knights of the Ordinary".’

‘Knights of the

Ordinary?’ said Donald, in a tone of enquiry.

‘Knights attracted to

their names epithets which characterised their

standing amongst their peers,’ Father Acosta

explained. ‘For example, one of Don

Miguel’s contemporaries, Gilbert de Mouton,

was known as Gilbert the Brave. Hugh de Chevalier

was known as Hugh the Wise. Many of the

island’s administrators were known by the

term “the Ordinary”. For example, the

person who managed the accounting for the

thirteen defensive towers funded by Martin de

Redin, Richard de Vere, was known as Richard the

Ordinary.’

‘What epithet was

afforded to Don Miguel?’ Donald enquired.

‘Initially he was

known as Don Miguel the Tedious,’ answered

Father Acosta. ‘Although after his wife ran

off with Philip the Well Endowed, he was often

referred to as Don Miguel the Sad Loser.’

‘I used to be an

administrator,’ confessed Donald, ‘and

my wife left me for someone called Philip, as she

said I was too tedious.’ Donald paused,

reflecting upon this coincidence. ‘Do you

believe in reincarnation?’

‘I am a Catholic,’

replied Father Acosta. ‘I believe that God

gives us each just one life. You are not the

first, however, to have this experience - to

become aware of a Knight and then to find

parallels between your life and his. Perhaps, on

a day like today, their voices, burned by the

Mediterranean sun into the very fabric of the

ancient structures on this island, are released

onto the wind and can be detected by those for

whom they have some sympathetic resonance. We

call this phenomenon the Daze of the Knights.’

‘Why was Don Miguel

known as “the Tedious”? asked Donald,

anxious to know more about this kindred spirit.

‘I believe he enjoyed

keeping meticulous records of all transactions

with which he was involved. He even took his work

home with him.’

‘There’s nothing

quite as satisfying as a neat column of

reconciled figures on a spreadsheet,’ Donald

empathised.

‘He liked to spend

hours at the entrance to the Great Harbour noting

the names of the boats that passed into and out

of the harbour,’ Father Acosta noted.

‘I think train

spotting is most interesting hobby there

ever could be.’ Donald volunteered a further

similarity from his own life.

‘He used to describe

the minutia of his everyday life in detail to

anyone who could not escape,’ continued

Father Acosta, pointing to a gravestone in the

floor of the Cathedral, just a few feet in front

of them. ‘That’s his tomb. Look at the

illustration that’s at centre, left.’

In common

with all the gravestones that comprised the

larger area of the Cathedral floor, Don

Miguel’s was inlaid with the richest marble

and porphyry in pietre dure. The image that

Father Acosta had indicated, depicted the Knight

holding forth on some issue, clearly of great

relevance to himself. Around him slumped his

audience, yawning or asleep. One knight even held

a sword to his own throat, clearly indicating

that a meeting with his maker would, to him in

that moment, be preferable to further attendance

upon Don Miguel’s discourse. In common

with all the gravestones that comprised the

larger area of the Cathedral floor, Don

Miguel’s was inlaid with the richest marble

and porphyry in pietre dure. The image that

Father Acosta had indicated, depicted the Knight

holding forth on some issue, clearly of great

relevance to himself. Around him slumped his

audience, yawning or asleep. One knight even held

a sword to his own throat, clearly indicating

that a meeting with his maker would, to him in

that moment, be preferable to further attendance

upon Don Miguel’s discourse.

Donald remained silent. The

parallels were beginning to feel a little

uncomfortable. ‘What happened to Don Miguel

in his later years?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know all

the details of individual knights,’ Father

Acosta replied. ‘Key aspects of his life may

be depicted on his gravestone.’ The Father

looked at his watch. ‘It has been

interesting meeting you,’ he said to Donald,

stifling a yawn, ‘but I must go about my

business.’

‘Yes, of course,’

said Donald. ‘Thank you for your time.’

‘Remember,’ said

Father Acosta before he turned to walk away,

‘that Don Miguel’s life is not yours.

You have the power to change the direction of

your own life.’

Donald thought about Father

Acosta’s words as he watched him walk down

the nave and disappear towards the Oratory.

Donald then turned and walked over to Don

Miguel’s gravestone. There were many small

illustrations upon it, presumably depicting

elements of the knight’s life. Donald noted

a garden which reminded him of his own membership

of the allotment society. Then there were a

number of small images showing various countries.

Perhaps those might parallel his stamp collecting

or even his annual, low cost, package holidays.

But what was this? At the

bottom of the gravestone were depicted bags of

money, then amphorae of wine, then young women in

various states of undress. It seemed to Donald

that Don Miguel had enjoyed a life altering

change of his fortunes in his later life, but

what had precipitated that? He looked at the

image just to the left of the money bags and then

withdrew his guidebook from his pocket. The image

was of a defensive tower with a small island

behind it, and a distinctive headland, beyond. A

very similar view appeared in his illustrated

guide. The caption read: “Wignacourt Tower,

St Paul’s Bay.”

~*~*~

There was

not a cloud in the sky, but Donald was glad to

escape the continuing wind as he entered

Wignacourt Tower on the following morning. There was

not a cloud in the sky, but Donald was glad to

escape the continuing wind as he entered

Wignacourt Tower on the following morning.

A very helpful middle-aged

woman gave Donald his ticket and some explanatory

literature on the origins of this imposing,

limestone-block defence - now the oldest coastal

defence post on Malta.

‘Does the name of the

Knight, Don Miguel de Cordoba mean anything to

you? Donald asked her.

Before she could reply, a

sudden gust of wind scattered many of the

remaining leaflets across the floor. The woman

looked towards the narrow spiral staircase in one

corner of the tower. ‘I think the last

visitor didn’t properly close the door to

the roof,’ she said.

‘I’ll make sure I

close it,’ said Donald as he helped her

collect the papers. ‘The wind can badly

disturb things in the upper chamber too.’

‘You’ve been here

before, then,’ the woman surmised.

‘No,’ said Donald.

‘How do you know that

the stairs to the roof act like a chimney for the

breeze?’

Donald reflected that it

was a good question, but of a type that was

becoming familiar and less remarkable to him.

‘Does the name of the Knight, Don Miguel de

Cordoba mean anything to you? Donald reverted to

the subject of his initial enquiry.

‘A moment ago I would

have said no,’ she replied, furrowing her

brow in thought, ‘but the name does seem a

little familiar, somehow, although I can’t

recall more than that at the moment.’

~*~*~

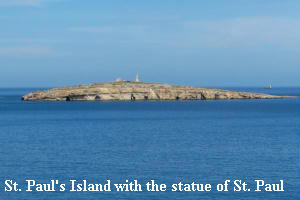

Donald

stepped onto the roof of the tower and closed the

door after him. He looked out across St.

Paul’s Bay towards St. Paul’s Island.

The white statue of St. Paul was clearly visible

on the island, half the height that the island

stood above the sea. Donald

stepped onto the roof of the tower and closed the

door after him. He looked out across St.

Paul’s Bay towards St. Paul’s Island.

The white statue of St. Paul was clearly visible

on the island, half the height that the island

stood above the sea.

Donald pulled his coat

about him to protect him from the wind. ‘The

second letter is in the well-shaft,’ he

heard himself involuntarily whisper.

It had always been one of

Donald’s skills as an administrator to focus

on analysing the particular matter of detail that

lay before him and not to become side-tracked by

excessive consideration of the broader context.

He therefore did not ponder on whatever mystical

link he might have with Don Miguel the Sad Loser,

and he did not think about how that connection

had taken him from the Upper Barrakka Garden to

St. John’s Co-Cathedral and then to

Wignacourt Tower. Instead he asked himself what

the second letter was, and where the well could

be found?

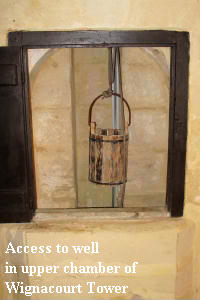

One possible answer to his

second question lay in the upper chamber, below

him. During the time of the Knights, water for

the soldiers who had been on duty in the upper

chamber had been drawn from a well below the

tower. In the wall of the upper chamber was a

door to a shaft within which hung a wooden bucket

that could be hoisted to and from the well below.

Donald opened the roof door

and began to descend the worn stone steps to the

upper chamber, pausing briefly to secure the door

behind him in the automatic, unthinking, habitual

fashion that he might have closed his own front

door.

Once in the upper chamber,

Donald stood at the well opening and placed his

hand inside. He touched the far wall and

stretched his arm and hand downwards across two

of the limestone blocks that formed the shaft, to

the point where he could feel a stone

protuberance. He knocked it sideways with his

palm, causing a small door in the block to open.

Finally he removed the sealed clay box from its

hiding place.

‘I found this in the

upper chamber,’ said Donald to the woman in

the lower room, handing the box to her. ‘I

think it might be important.’

~*~*~

Epilogue:

The rest of this story is

now, of course, history.

It has since been widely

reported how Don Miguel de Cordoba discovered two

scrolls at St. Paul’s Bay, Malta. These

letters had been written by St. Paul during the

three months he spent on the island following his

shipwreck in 60 AD.

The letters had confirmed

the exact details of his shipwreck, but had also

contained quotations by Jesus that had been

contrary to Church teachings. Don Miguel had

become concerned that the Pope might, as a result,

destroy the artefacts, and so had revealed the

existence of just one.

The Church had taken the

first scroll, suppressed the heretical opinions

of Jesus that it had contained and sealed the

document in the vaults of the Vatican. Don Miguel

had been been paid a king’s ransom

ostensibly for his discovery, but also for his

silence. He had concealed the second letter in

Wignacourt Tower, together with a note by himself

explaining the above, for discovery in some more

enlightened times.

Donald was credited with

the discovery of Paul’s second letter and

the note containing Don Miguel’s explanation.

The modern Order of the Knights of St. John,

known as the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order

of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta,

based in Rome, were required by ancient covenant

to award him five million pounds for the find.

The rediscovered letters

were, in common with their predecessor, quickly

consigned to the vaults of the Vatican, so it

remains unclear as to exactly which elements of

the teachings of Jesus are considered to be un-Christian

by the Catholic Church. Fortunately the Church

has, thus far, chosen not to posthumously

excommunicate either Jesus or St. Paul.

Donald considered the

comments of Father Acosta that he need not live

his life to the precise pattern of that of Don

Miguel de Cordoba. However, the final

illustrations on the Knight’s tomb -

numerous wine amphorae and endless young women in

various states of undress - seemed to him to

constitute a satisfactory life plan. He had been,

he thought, a little conservative for too much of

his life. In the end, he deviated slightly from

the exact images by buying wine in cases due to

the modern shortage of amphorae.

Finally, since the whole

story was reported in Time Magazine, the

Upper Barrakka Garden is often crowded in March

and April on days when the cool Mediterranean

wind blows just a little too briskly for comfort.

Some visitors, perhaps, hoping that a voice from

long ago may speak on the breeze and transport them

into the Daze of the Knights.

|